Introducing Making A Scene: "All Her Fault" scene deep dive

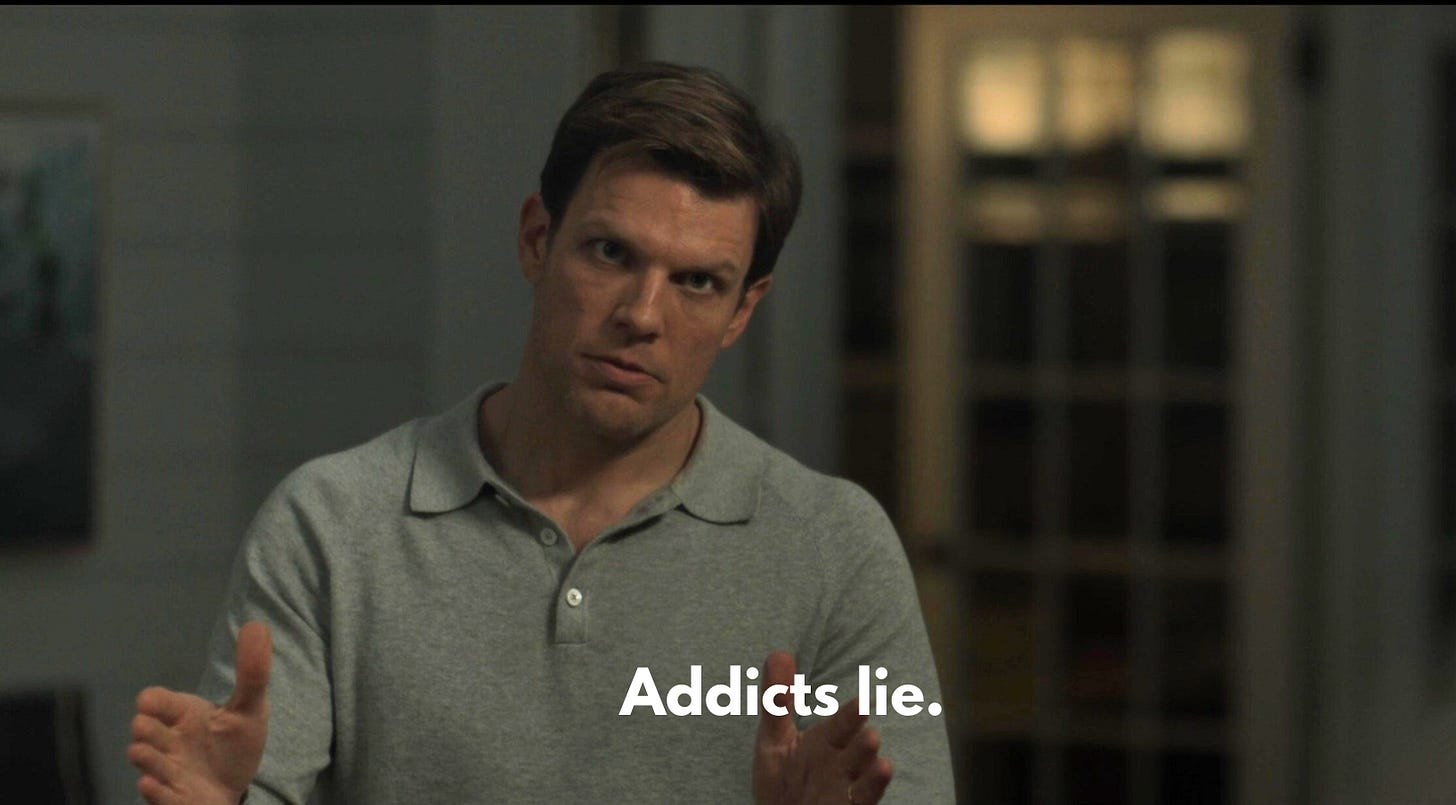

A (mostly) spoiler-free look Peter's "addicts lie" scene in episode five.

Welcome to Ask a Sober Lady! This is a reader-supported publication. All posts are free, but paid subscriptions keep the newsletter alive. If you think this is a valuable resource and want to support my work, consider upgrading to a paid subscription or leaving a tip.

I have strong opinions about fictional depictions of substance use, addiction, and recovery, so I am excited to kick off this newsletter segment tentatively called...Making A Scene.

One challenge with this idea is balancing coverage of newish TV and movies that are topical or somewhat in the zeitgeist with the risk of spoiling shows for readers. To that end, I’ll include a note at the top of each of these with information about the show and episode I’m discussing, whether it contains spoilers, and whether those spoilers are central to the plot.

For this inaugural post, I’m looking at one scene in episode five of the miniseries All Her Fault. It’s a show about a child who goes missing and the chaos that ensues. The part I’ll discuss contains one (largely insignificant) spoiler and doesn’t give anything away about the mystery at the heart of the show.

The players: Marissa Irvine (Sarah Snook) and her husband, Peter (Jake Lacy); Marissa’s best friend and business partner, Colin (Jay Ellis), who is in recovery for gambling addiction; Peter’s little sister, Lia, who is in recovery for an unspecified “pill” addiction.

Peter and Lia have a brother, Brian, who is disabled from a spinal injury that occurred when he was a child.

The scene: Marissa discovers that Colin, Lia, and Brian are keeping something from Peter and her. At the same time, Peter finds that Brian’s recently refilled prescription for pain medication–which he hates taking–is down to the last few pills.

Pushing Colin to disclose what the others have been hiding, Colin admits that he and Lia have been dating for several months. Naturally, this is the exact moment Peter walks into the room, fresh off his discovery of Brian’s nearly empty pill bottle.

I’m only looking at about a minute of screentime, so I’ve written out the dialogue (I’m hoping to figure out a legal-ish way to embed clips—if you know of one, please let me know). The interaction feels very real; some version of this confrontation has played out countless times among people in recovery and their loved ones.

Peter: You’re dating my sister?

Colin: Shit....shit. Um. Yeah. And I know that it might be weird that I am involved with your sister—

Peter: Uh, no, no, I don’t…I don’t care about that. I’m not a Neanderthal. And my sister’s an adult. She can… she can date who she wants.

[Pointed silence]

Peter: I do care that you’re both addicts, though.

Colin: OK, we’re… we’re not the same kind of addict, Peter.

Peter: Fine, yeah. You’re a gambling addict, and she likes pills. But you’re not really supposed to date each other, right?

Colin: No, it’s…it’s not like a rule.

Peter: No, but it’s not exactly encouraged, is it?

Colin: No.

Peter: No. Because it puts you both at risk for relapse.

[Quick note: This is likely a reference to the oft-repeated advice that people in their first year of recovery should avoid dating. It’s not specific to dating other people in recovery, though obviously, two people in early recovery could be seen as twice as risky. In my opinion, it’s advice rooted in truth that’s been warped into dogma, but that’s a discussion for another day.]

Marissa: I… I trusted you. I… I… I went into business with you. And I put my name next to yours on a wall, because I trusted you, Colin.

Colin: Listen, my personal life has nothing to do with our business. I would never put that at risk.

Marissa: Well....it has in the past. I mean, are you...are you gambling again?

Peter: No. He’s not the one who relapsed...Lia is. Brian’s pills are missing.

Marissa: What?

Peter: Yeah.

Colin: No, listen, hey. Lia did not take those—

Peter: How the fuck would you know?

Colin: Lia did not take those pills.

Peter: Right. They just got up and left on their own?

Colin: I don’t know. Maybe it’s a misunderstanding. Have you even asked her if she took them?

Peter: Why would I? Addicts lie.

It was at this moment that I knew I wanted to write about this scene for the newsletter. The way Peter growls these two words—self-righteous, condescending, and exasperated is likely familiar-bordering-on-triggering to anyone who has been on the receiving end of them. And whether or not they’ve articulated them in the same way, the words have certainly crossed the mind of people whose trust has repeatedly been broken by a loved one’s chronic substance misuse.

It’s a statement that’s wildly dismissive, hurtful, and stigmatizing—especially when weaponized against someone in recovery. Unfortunately, it’s also undeniably true for the vast majority of people actively addicted to substances.

I don’t believe that people who have substance use disorders are fundamentally dishonest or have some innate moral failing that makes us untrustworthy. For one thing, lying is hardly exclusive to “addicts.” Humans lie. Not always, and not necessarily with the same consequences that people misusing substances might, but everyone does it a little, at least some of the time. More importantly, in the case of people with addiction, it’s an understandable response to protecting something that feels necessary to their survival. (I’m not saying it’s ethical or good. But it is understandable.)

At least, that’s how it seemed when I was in the throes of addiction. Drinking the way I wanted required near constant lying to myself and others. Whether it was telling myself it was the last time I was going to drink before work or telling my boyfriend that I hadn’t been drinking at all, deception was part of how I had to exist. It felt awful and necessary, and I was sure that the only thing worse would be telling the truth.

Because what’s the alternative to lying? We tend to respond to people with addiction with an ultimatum: We demand they “get help”—which often means quit using—or be cut out of their loved one’s lives.

Having been the “addict” in this scenario, being forced into that choice feels painfully unfair and even cruel. It feels like your loved ones are punishing you for doing the only thing that allows you to make it from one day to the next. When you cannot imagine your life without the thing to which you’ve become addicted, protecting it feels no different than protecting one’s source of water, food, or shelter.

It’s not uncommon for people to lose those actual necessities in the pursuit of the thing that feels even more vital to existence. It’s why so many people with addiction end up isolating—both to keep their use hidden from others who might try to intervene and as a way of cutting oneself off before everyone else does it first.

But I’ve also been the person to whom a supposedly sober loved one lies. It’s heartbreaking and infuriating. If pills or alcohol or whatever they’ve historically misused go missing—even if there are no signs of the culprit—it’s hard to stop your mind from going to what seems like the most logical explanation. Denials are hard to believe after previous incarnations proved to be lies.

There is no winning here. It’s unfair to immediately assume the person in recovery is lying, and it’s unfair to ask loved ones to ignore a long history of dishonesty and give the person the benefit of the doubt.

Making matters worse is that each side can exacerbate the other: Constantly feeling under suspicion by family and friends is unlikely to help anyone get or stay sober, and not saying sober is unlikely to build trust among the people who think you are.

So what’s a family to do? There’s too much other stuff going on with the Irvines to continue using them as an example, plus Peter says everything in the most dickish way possible (also not a spoiler), but similar scenarios are very common in families where one or more people are in recovery from addiction.

In thinking about the scene and what I wanted to say about it, I kept coming back to Peter’s motivation for being such an aggressive ass about it. There’s no world in which Lia (hypothetically) stealing pills after the disappearance of Irvines’ child has anything to do with that incident. Peter is mad because he believes his sister is using again and is being lied to about it. There are emotional stakes for Peter, but no immediate practical consequences.

The stakes matter. They can also be a useful guide for how hard to push the issue. For example, if my sister suspected I was drinking again and I also happened to be a frequent, solo caregiver to my nieces, she’d need to know what I was up to because it directly affects her children’s care. Ideally, she’d say something like “I need to know if you’re drinking again—not because I’m going to judge you or tell you what to do, but because I need to know that the girls are safe under your supervision.” The stakes are high.

If the stakes are, “I’ve seen this show before, and I’m worried about where this road eventually leads,” there’s less urgency. The motivation for the confrontation matters, as do the practical implications of someone’s substance use. Very often, loved ones are so used to searching for clues and “proactive” confrontation that they lose sight of what’s actually helpful in that moment. They want to know because they want to know. They’re determined to find out if they’re being lied to just so they can call their loved one on it, not because there are any immediate stakes to that lie.

If I were to start drinking again, there’s only a tiny window in which I could realistically lie about that before the evidence would give me away. It’s not true for everyone, but it’s true for most people I know on the severe end of the substance use disorder spectrum. I know firsthand how hard it can be to stop searching for clues and deception when you’re scared and just want to protect your loved one from themself. But unchecked by reality, those instincts can metastasize into an unruly beast that does more harm than good.

Corralling that beast is much easier said than done, which is exactly what made this depiction so infuriatingly realistic.

If you enjoyed this post, please like, comment, or share it. Doing so helps others find the newsletter! Also, let me know what you think of the new segment and if you have suggestions for future Scenes.

Send questions and feedback to askasoberlady@gmail.com. By sending a question, you agree to let me reprint it in the newsletter with your name redacted or changed. Emails may be edited for length or clarity.

I’m not a doctor or mental health professional, so my advice shouldn’t be construed as medical or therapeutic. You are free to take or leave it.

I really like this - both the premise of looking at these depictions on screen/in books (which are often pretty crude, and bug me as a result), but also the nuance with which you’ve unpacked it. Like many important things in life, this stuff is vastly complicated, and deserves far more care than just being a plot point.

Always to the point and always a pleasure to read. Thanks.