Is relapse always a part of recovery?

The inaccurate truth of recovery slogans and how to get out of cartoon quicksand.

Welcome to Ask a Sober Lady! This is a reader-supported publication. All the posts are free, but paid subscriptions allow me to keep writing them. If you’re in a position to upgrade your support, please consider doing so. Either way, I’m happy you’re here!

Dear Sober Lady,

I always hear the phrase “relapse is a part of recovery,” and it seems weird to me. I know that’s not true for everyone. Where does that saying come from, and do you think it’s accurate?

—Curious

Hi Curious,

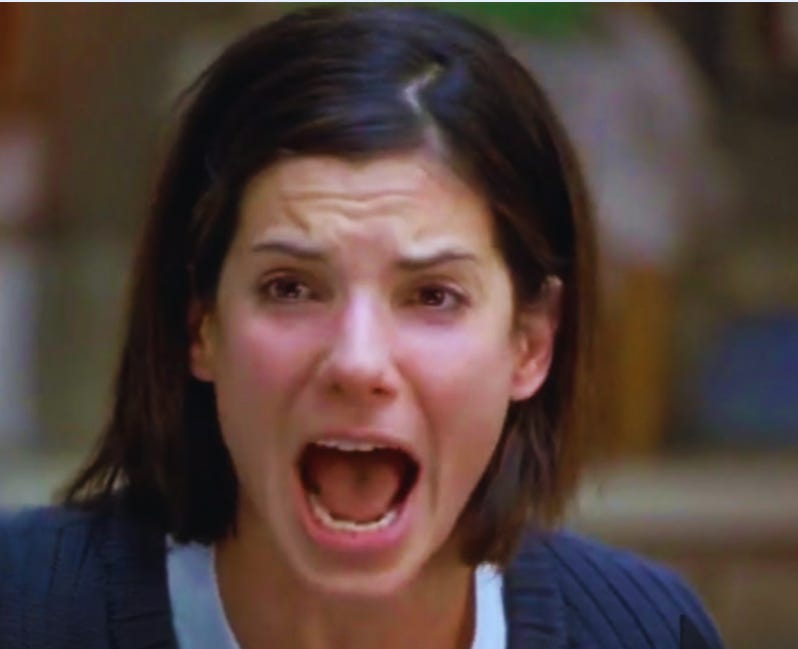

There’s a scene in the movie 28 Days where Gwen, played by Sandra Bullock, is newly in rehab and profoundly unhappy about it. She doesn’t know what she needs, but she’s certain it’s not sitting in a group of twitchy weirdos talking about their feelings. At one point in the aforementioned group, someone offers the quintessential 12-step platitude and tells her to take things “one day at a time.” In response, she blurts out, “I am so tired of the way you people talk! I mean ‘One day at a time?’ What is that!? Like two, three days at a time is an option?”

Twelve-step recovery is famously slogan-laden; posters blaring First Things First, Easy Does It, Let Go And Let God, and of course, One Day At A Time line the walls of countless AA meeting rooms. Each saying can be helpful or annoying (and often both), depending on the person and their situation. To my knowledge, “relapse is a part of recovery” isn’t specific to twelve-step recovery, but it certainly makes the rounds in TSR and non-TSR circles alike.

It’s a saying that, until recently, used to bother me. It’s objectively untrue, I thought, so isn’t reiterating the normality of relapse a bit self-defeating? The phrase triggered two parts of my personality that are not necessarily the best: the instinctive need to be contrarian and a tendency to hyperfixate on the literal.

As a journalist with a background in librarianship, I can fact-check and nitpick with the best of them. But in this case, nitpicking meant I was forgetting a lesson a brilliant writer and teacher, Pam Houston, once told me about non-fiction: Some fictions tell a truer story than the facts. (Apologies to Pam, I’m paraphrasing, and poorly.)

I remembered this recently while reading a book about the writing of the Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous. (Despite not being involved in AA for over a decade, I remain fascinated by its history and influence on society.) Much of AA’s origin story isn’t, strictly speaking, factually accurate.

What questions do you have about substance use and recovery? What topics would you like me to address in the newsletter?

Take the famous story that appears at the beginning of the Big Book. Bill Wilson’s friend, Ebby Thatcher, visits Wilson and finds him drinking alone at his kitchen table. Thatcher explains how he was on the verge of being sentenced to prison for “drunkenness and alcoholic insanity,” but found sobriety through the Christian Oxford Group. Wilson is initially horrified by his friend’s religious conversion, and then reluctantly intrigued by his sobriety. Only that’s not quite how it happened.

Instead, the visit was a somewhat chaotic dinner with the men, their wives, and a woman who was living in the Wilsons’ upstairs apartment. It was Wilson’s wife, Lois, who prompted Thatcher to talk about what he’d been up to; Wilson only showed a casual interest in Thatcher’s sobriety when the two men were walking to the subway after dinner.

But a one-on-one conversation over a kitchen table, while one man drinks and the other extols the freedom of his unexpected and miraculous sobriety, is a much better story. It is simple, straightforward, and retains the essential facts. It is not a piece of journalism; it is a parable-like origin narrative for an international mutual aid organization characterized by one alcoholic talking to another. In this way, the kitchen table story is arguably truer—though undeniably less accurate—than the historical version of events.

The same is true for the phrase “relapse is a part of recovery.” If we go by the facts, it’s obviously not true for everyone. What is true is that recovery is never linear. No one gets sober and finds each day more blissfully serene than the last. Whether the “relapse” in question looks like a bottle of vodka, depression, or punching a wall isn’t really the point. The point is simply that experiencing lows in recovery is normal and unavoidable.

Their nonspecific simplicity is why it’s so easy to mock or become irritated by these slogans. It’s also why they’re useful. They don’t exist for moments of quiet, thoughtful reflection. You’re not meant to calmly ponder their timeless wisdom. They’re designed for the days your boss yells at you, and someone rear-ends your car, and your dog gets sick, and a drink sounds like the answer to everything, and there’s a liquor store right there.

When you feel like you’ve stepped into cartoon quicksand and are rapidly sinking into the abyss, a cheesy slogan is your best friend. Your brain is in survival mode; you’re sweaty, panicky, and miserable. You can’t slow down long enough to mentally walk through your history with alcohol and the negative consequences that resulted. You can’t call a friend or your therapist because there’s sawdust in your throat and you’ve forgotten how phones work. All you know is that a drink sounds like the solution to every problem. You’re grasping in the dark for a lifeline—anything that will stop you from being swallowed up by the forces beyond your control. So you remember that you can only take it one day at a time. Or that relapse is a part of recovery. Hold on to that needlepoint pillow of a saying until your heart slows and you can breathe again. You might be surprised how effectively it carries you safely to the other side.

Some free subscribers have requested a way to support my work without upgrading to a monthly paid subscription. A link to my tip jar will be included at the end of each post for those who would like to donate. As always, please do not feel any pressure to do so; I’m grateful for every reader, paid or unpaid.

Send questions and feedback to askasoberlady@gmail.com. By sending a question, you agree to let me reprint it in the newsletter with your name redacted or changed. Emails may be edited for length or clarity.

I’m not a doctor or mental health professional, so my advice shouldn’t be construed as medical or therapeutic. You are free to take or leave it.

Very thoughtful response to an important question. I think relapse is part of some recovery stories (just like divorce is part of some recovery stories, or unemployment, or … other realities of living a human story). I think, too, that different factors contribute to “relapse”; I have a family member who couldn’t maintain his sobriety until his anxiety & depression was addressed as aggressively as his drinking. I think the danger lies in judging one’s relapse as the fault of “not working the program.”

I’m on day 34 and, while I love hearing that I won’t be a failure if I relapse, I’m worried that message (which I am grateful to receive in NA) will somehow give me permission to drink again. But then again, if I was constantly told relapse would mean I failed, I might be more inclined to give up when things get rough. So much to think about right now LOL. ODAAT, I know.