Ozempic, psychedelics, and magic bullet cures for addiction

"I have been stung by their talk as by hornets, and have been driven to solitude to avoid the fools."

Welcome to Ask a Sober Lady! This is a reader-supported publication. All the posts are free, but paid subscriptions allow me to keep writing them. If you’re in a position to upgrade your support, please consider doing so. Either way, I’m happy you’re here!

This week, STAT published a story with the headline, “Ozempic for addiction: How an elite rehab center is using GLP-1s to ‘obliterate’ all kinds of cravings.”

I’m excited about any medication that might help people recover from the hell that is addiction. But the hype around GLP-1s and substance use disorders is reminiscent of the media coverage touting psychedelics as a surefire addiction ‘cure.’

Like psychedelic-assisted therapy, the possibility of GLP-1s “obliterating” or otherwise curing addiction has gotten a lot of buzzy press and generated interest among people who are struggling with their substance use. The fact that these drugs aren’t FDA-approved (for addiction) means health insurance won’t cover them; the only people who can access them are those who can afford to pay thousands of dollars out of pocket. I worry that media hype combined with barriers to access creates an environment where people go to great and potentially dangerous lengths to obtain these treatments.

I’m sure that these substances have helped people recover from substance use disorders. There’s nothing wrong with using medication or other substances to help them get and stay sober (I’m one of those people!). But headlines that imply there is a singular cure for addiction are dangerous.

Medicine Men

“I am aware that the efforts of science and humanity, in applying their resources to the cure of a disease induced by a vice will meet with a cold reception by many people.” Benjamin Rush

More than 240 years ago, Benjamin Rush, a physician and one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, described his belief that alcoholism was a medical disease, not the result of moral depravity or mental illness.

Though the idea would not reach the mainstream in the United States for more than a century, what’s notable is that the identification of a disease—even at the earliest stages of that identification—is always bundled with the hope for a ‘cure.’

It makes sense, on an instinctive and even linguistic level. We like ease. Ease is good. Disease is the opposite. Disease is bad. Curing a disease implies a return to ease, and isn’t that nice?

Benjamin Rush sure thought so. He claimed to have cured one case of what we’d now call severe alcohol use disorder by adding a highly toxic substance (tartar emetic) to the afflicted’s alcohol. This induced an acute bout of vomiting which, Rush proudly proclaimed, resulted in the afflicted developing a two-year aversion to the sight or smell of alcohol. Aversion-therapy for alcohol use disorder remains one of the most tried and least true methods, including more than two centuries later, courtesy of Antabuse, a pill that makes anyone who ingests it with alcohol violently ill.

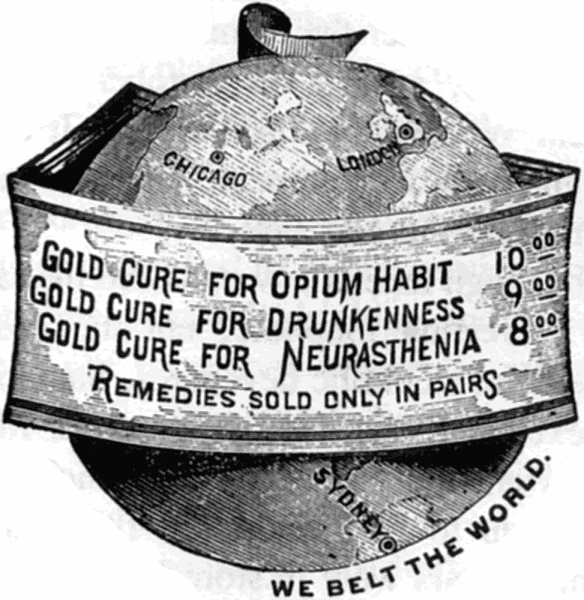

Shockingly, alcohol use disorder still exists. Other purported ‘cures’ over the years include injections of bichloride of gold (a compound found in gold), cocaine, morphine, belladonna, vegetables, religious conversion, water, and a concoction that was 75.5 percent alcohol. The list goes on.

Why an ‘addiction cure’ isn’t a thing

There’s a reason doctors no longer use the term ‘addiction’ and now say substance use disorder. They understand that a range of disorders exist under the SUD umbrella and that within those individual disorders, there’s a range in severity. As a writer, ‘substance use disorder’ or ‘alcohol use disorder’ is rage-inducing clunky phrasing. But it’s also important. It reminds us that what we think of as ‘addiction’ or even ‘alcoholism’ is not a single medical condition and thus is unlikely to have a single cure.

What questions do you have about substance use and recovery? What topics would you like me to address in the newsletter?

For many people, medication (or psychedelics, or probably even Ozempic) may be enough to treat their SUD completely. But nothing works for everyone. People with AUD can have similar symptoms, but the specifics of how that disorder came to be will vary from person to person. Genetics, biology, environment, trauma, and countless other factors are involved. I don’t mean to imply that each component needs its own treatment, only that there is unlikely to be ONE cure that works for everyone.

The problem with medical professionals proclaiming they’ve found an ‘addiction cure’ is twofold: first, when the inevitable happens and someone isn’t cured, the blame is often—intentionally or otherwise—shifted to the patient. (Ever had an antidepressant not work, and the psychiatrist writes that you “failed” the medication? It’s commonly used clinical verbiage.) Second, what’s a patient to do when the magic cure doesn’t work for them? How are they supposed to trust addiction medicine? In 1880, after seeing specialist after specialist in the burgeoning field of addiction medicine, one patient wrote the following:

I have borne the most unfair comments and insinuations from people utterly incapable of comprehending for one second the smallest part of my suffering, or even knowing that such could exist. Yet they claim to deliver opinions and comments as though better informed on the subject of opium eating than anybody else in the world. I have been stung by their talk as by hornets, and have been driven to solitude to avoid the fools.

Addiction is the thief of hope. It pulled me into a vortex of self-loathing, despair, secrecy, and isolation. Those feelings were part of what I needed to untangle when I got sober. Talk of magic bullets and cures can give people hope, but it can also make them overconfident, complacent, and—if the treatment doesn’t yield the expected results—brutally disappointed.

For me—and many others who’ve had substance use disorders—recovery arose through multiple treatments and methods. Medication, therapy, AA, changing my environment, all of it was necessary to make the sobriety stick. I hope that for some people, sobriety truly is one injection away. But if that’s not you, don’t worry. There are plenty of options (and combinations of options) to try. There is no end to this road. There’s just the path you haven’t found yet.

Some free subscribers have requested a way to support my work without upgrading to a monthly paid subscription. A link to my tip jar will be included at the end of each post for those who would like to donate. As always, please do not feel any pressure to do so; I’m grateful for every subscriber, paid or unpaid.

Send questions and feedback to askasoberlady@gmail.com. By sending a question, you agree to let me reprint it in the newsletter with your name redacted or changed. Emails may be edited for length or clarity.

I’m not a doctor or mental health professional, so my advice shouldn’t be construed as medical or therapeutic. You are free to take or leave it.

Thank you for this piece. I read it with great interest. I’ve been sober for 7 years, and in my experience, it’s taken a mix of things: medication, therapy, support, changes in my work environment, and shifts in my own behavior. My willpower definitely played a huge role, but I know everyone’s path is different. Thanks for highlighting that there’s no one-size-fits-all solution.

I was on ozempic for weight loss purposes because I was developing chronic health conditions like high blood pressure. My experience with the GLP-1 indicated what others have reported: that it has numerous benefits beyond appetite suppression, including helping me limit impulse spending and curbing mental food noise, another other benefits. I could definitely see benefits of the drug for some people who grapple with addiction.

But what happens when they come off it? Unless they intend to be on it for life. At least for weight purposes, I knew I had to set up healthy exercise habits and change my eating patterns while on ozempic so I wouldn’t gain it all back when I came off the drug.

But people with substance use disorder who use GLP-1s may not get the same help in terms of setting up their environment for the best chances of maintaining sobriety in the long run. That would be my main concern.