The Halcyon Days of Barfing in Trash Cans

It’s dangerously easy to romanticize the early years of my substance use. Good thing I have embarrassing journal entries to remind me of just how bad it was!

I was “cleaning up my office” over the weekend—by which I mean moving things from messy piles into slightly neater piles—when I came across a journal I had in high school. Being an absolute masochist, I decided to crack it open and take a trip down memory lane. In 2000, I was a 15-year-old freshman at an academically rigorous private school, and floundering. Scraping by with Cs on a good day, I felt like I wasn’t as smart as my peers, some of whom had taken the SATs “for fun” as freshmen and come away with near-perfect scores. I did have one skill the others didn’t: I excelled at finding and consuming alcohol.

Hello friends, send me your alcohol/drug use and recovery questions! We’ve got the election, holidays, and New Year’s coming up, all of which can be tricky for people trying to moderate or abstain from booze and other drugs. This is a judgment free space—no question too small or silly! Click the button below to send me an email.

When I think about the challenges of that first year, academics, a tumultuous home life, and my terrible acne come to mind. Two and a half decades later, I tend to think of the drinking part of my 15-year-old life as something that wasn’t that bad yet but a harbinger of things to come. In my mind, most of those early drinking years were characterized by freedom and euphoria—itching to get out of my house and, once successful, partying with a reckless abandon that let me forget everything else that was shitty in my life.

Then I opened that spiral-bound notebook. Amidst all the teenage melodrama and cringe that jumped out at me from the pages of that dusty journal was a surprisingly lucid thread about how distinctly abnormal my drinking was—and how it was already damaging my relationships. I’d forgotten that word of my ferocious thirst for alcohol—and drive to quench it by any means necessary—had gotten back to some of my friend’s parents. I was quickly developing a “bad kid” reputation.

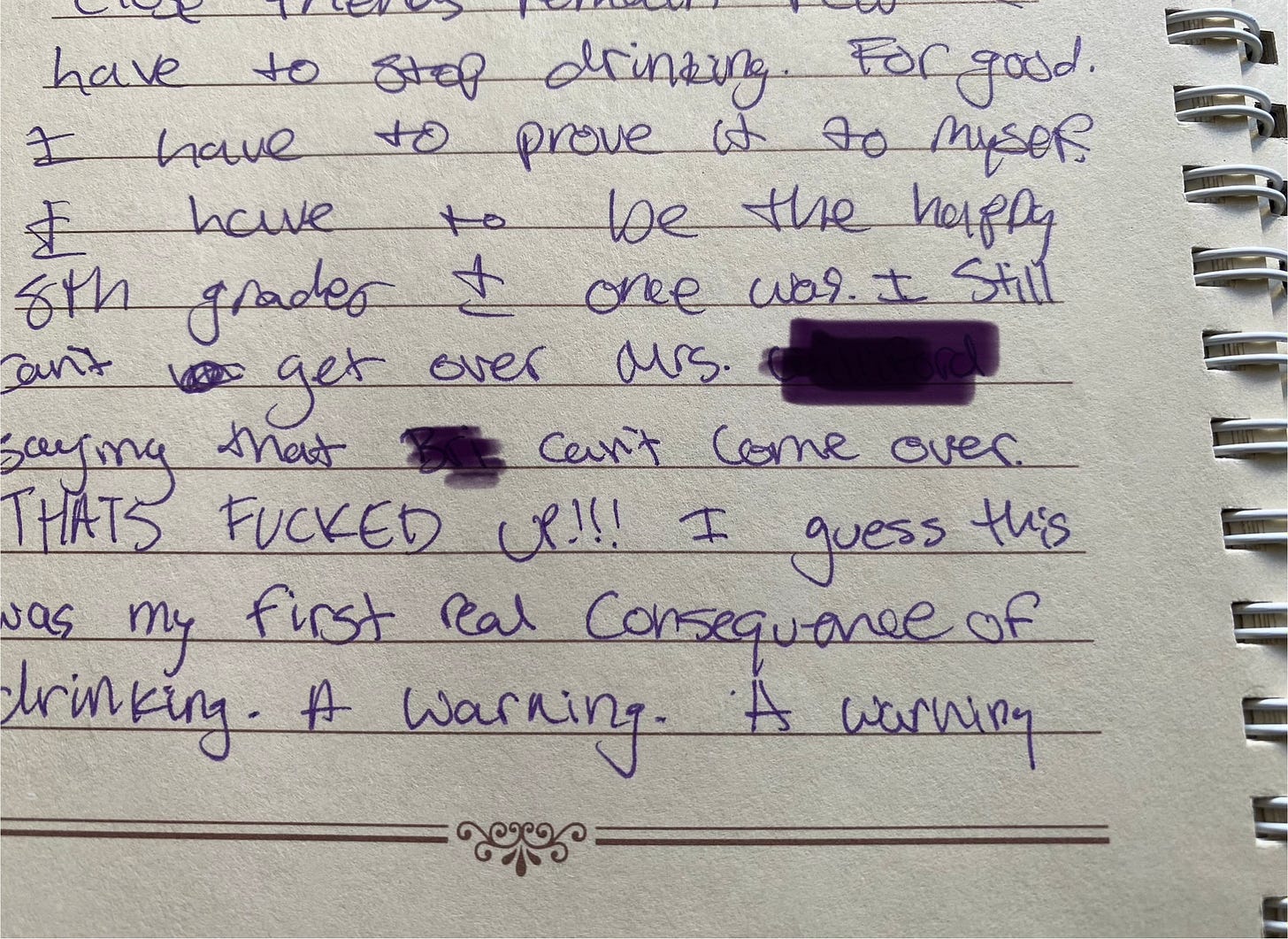

I wrote:

“I have to stop drinking. For good. I have to prove it to myself. I have to be the happy 8th grader I once was. I still can’t get over Mrs. [Redacted] saying that [her daughter/my friend] can’t come over. THAT’S FUCKED UP!!! I guess this was my first real consequence of drinking. A warning. A warning.”

Aside from the fact that there is something very funny and bleak about trying to go back to “the happy 8th grader I once was,” the entry is painfully self-aware.

“I have to stop drinking. For good.” My father had not yet found his way into recovery, so I was only vaguely aware of AA and the notion that some people can’t moderate alcohol use and, thus, are better off abstaining entirely. And yet, somehow, I already had a feeling that’s how my story might end.

“I have to prove it to myself.” This is especially notable in context. I didn’t say I had to prove it to my friend’s mom or my friends; I seemed to understand that this was an internal battle—one I wasn’t sure I could win.

“I guess this was my first real consequence of drinking. A warning. A warning.” Obviously, it was not a warning I heeded. But knowing everything that happened over the next decade, it’s amazing how clearly—and early—the writing was on the wall.

It’s dangerously easy to romanticize the early years of my substance use. To remember the feeling that I became addicted to, the feeling that all I needed to be truly happy was to stay exactly the right amount of drunk. Decades later, it can be hard to remember that—whatever I may have felt—it wasn’t reflective of my reality. That, however happy I was when I had the right amount of booze and freedom, foreboding things were happening on the periphery that I was too drunk to see. Threads that connected me to important relationships were fraying; every time I drank, I turned into a bigger and bigger bull in an increasingly fragile china shop.

If I’m honest, there’s no time in my drinking life where my alcohol use wasn’t causing serious problems. Parents distanced their kids, I pissed off or scared friends with my antics, and I got kicked off trips because it never even occurred to me to follow the one rule: don’t drink.

I resented anyone who scrutinized my alcohol consumption and did my best to throw them off the scent. I became a simulacrum of a party girl—someone who lived for FUN. I wanted to create the impression that drinking was just a byproduct of my search for the next party or late-night escapade and not—as it truly was—the reason for it. If I could exist as the archetype, I could obscure my alcoholism in the frenzy of the persona’s other traits: a brash, loudmouth, adventure-seeker. It wasn’t an effective strategy.

I remember being at a party freshman or sophomore year when a friend of mine, who was typically a very mild to moderate drinker, ended up getting absolutely sloshed. She couldn’t stand up particularly well, so two of our other friends had her by each arm and were walking her home. As she ambled across the patio to leave, she slurred, “I feel like Katie Mac.” Everyone laughed. I went into the bathroom and cried. I knew that no one was laughing to be cruel; she was simply articulating the reality that we all knew to be true: at some point, someone would be carrying me home.

The holidays are approaching, and it’s particularly easy for me to romanticize the drinks of Christmas past. To feel envious of the people who don’t have to feel bad about imbibing more than they typically would because they won’t wake up with a burning compulsion to do the same thing again. There’s nothing wrong with that envy—it’s an honest and normal reaction to being unable to have something I want.

It would, however, be wrong to try to convince myself that there’s some scenario in which that’s possible for me. That my drinking hasn’t always—from the earliest days—been a god that demanded sacrifices. Friends, work, relationships, self-esteem, health—with me and alcohol, there’s always a cost. The beautiful thing—the thing that helps keep me sober—is knowing there’s nothing in my life I’m willing to risk for a drink.

Send questions and feedback to askasoberlady@gmail.com. By sending a question, you agree to let me reprint it in the newsletter with your name redacted or changed. Emails may be edited for length or clarity.

I’m not a doctor or mental health professional, so my advice shouldn’t be construed as medical or therapeutic advice. You are free to take or leave it.

My heart goes out to you…when you cracked opened the diary of your youth and saw how even then you could read the writing on the wall…or when you recounted the scene with your friend who was drunk and joked at your expense. Oh I’ve been there and I’m reaching through these electromagnetic waves with a mighty hug. Just last year (my first year sober when I decided to do some personal excavating) I opened the diaries of my 20s and learned that I went to AA once (an experience I had no recollection of until rereading some of those piercing details). I almost fell off my chair! I write about in my post “Drunk Journaling: Ghosts of AA Past and Present” if you’re interested. But all this to say, I don’t think a post on Substack has resonated more and I’m grateful I came across your account!

I appreciate your photoshop efforts